Dada and the idea

Dada was an artistic and literary movement, lasting from 1916 to 1922, that formed in Switzerland,

in reaction to the horror of World War 1.

The Dadaists believed that western cultural, artistic and political systems had inevitably

culminated in the carnage of the Great War. In response, they rejected all cultural constructs

- everything, past, present and future – and declared, ‘Art is dead’. More than iconoclasts,

they wanted to tear down all social andartistic norms and recreate society from scratch.

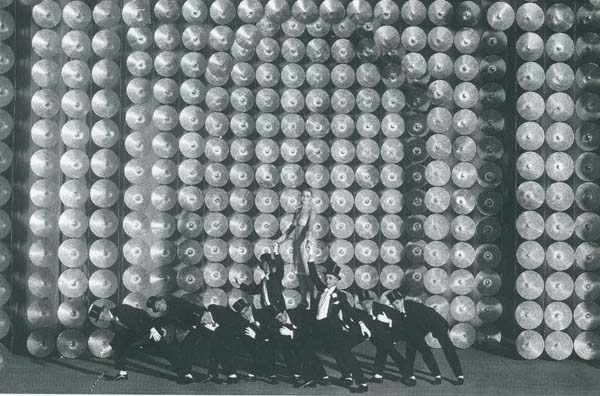

Dada started in the Cabaret Voltaire, opened by Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings in Zurich 1916.

Switzerland was neutral in the conflict and was a refuge for artists and, indeed, anyone

who was able to escape the nightmare of the war. Through the use of theatrical events,

Dada used opposites, contradictions, paradoxes and ironies to lampoon and

debunk all aspects of bourgeois society.

Dada continued in the artistic direction begun by other avant-garde movements such as Fauvism, Expressionism Cubism, Futurism and Constructivism. The artists who shaped the movement combined all of these styles in an eclectic mix, making Dada difficult to define. However the artists and the work they created were tied together by one concept - that the idea was the message, not the depiction or artifice.

Dada laid the groundwork for abstract and performance art. It served as a prelude to surrealism, pop art and postmodernism in general. Nearly all the famous art movements since the 1920s have been directly influenced by or are directly descended from the ideas of Dada.

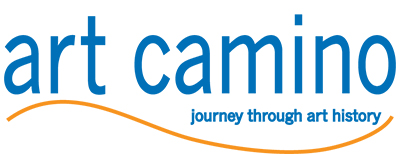

Through the publication of manifestos, magazines, poster poems and collages, Dada deeply influenced graphic design and advertising. Graphic design across the world is still changing and evolving as a result of the freedom afforded by the use of juxtaposition, mixing images with text, and free form typography that Dada explored.

In literature, Tristan Tzara moved beyond Symbolism. Using automatist writing he heralded the stream of consciousness of William Burroughs and the Beat Generation. Blending together various forms of human expression, poetry readings, performances and manifestos, the Dadaists invented the ‘happening’, of which the Burning Man festival in Nevada is perhaps the most famous example today.

The influence of this short-lived movement exploded across the world to become the inspiration - whether consciously recognised as such or not - of most post modern and contemporary artists emerging since then.

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp created the single most famous Dadaist work, titled ‘Fountain’, which was first exhibited in New York. ‘Fountain’ is a ceramic urinal signed R. Mutt, 1917. The provocative act of displaying a utilitarian manufactured object as art was pure Dada. It mocked the artistic community, the viewers and society in general. It said that all art is subjective and contextual.

It is this implicit statement that has continued to resonate with artists from then until now. Art was freed from artifice. No longer did it need to be linked to execution but only to meaning. Finally, the work that the Impressionists had begun came to its logical conclusion. Postmodernism was born.

.

Conceptual not ‘retinal art’

Vernacular European art, like Eastern, aboriginal Australian, American and African art all are essentially non-figurative, evoking abstract and metaphysical ideas. The European imagining of high art from the Renaissance onward, concentrated on classical depiction and narrative through figurative imagery - a king riding a horse to victory or a saint being touched by a miracle. This thinking relegated non-figurative depictions to quaint folk or decorative art.

However, driven by science, new philosophical treatises and the influx of Eastern and African art into Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, European art found radical new avenues to pursue.

.

The Impressionists moved away from depicting narratives targeting the viewer.

Instead of painting recognisable scenes or people, they attempted to capture light, movement and the passage of time. They used visible brush strokes and blurred colours rather than contours or lines. Moving away from accurate depictions they instead were concerned with the transitory moments that make up human experience.

They painted ordinary people or living landscapes and attempted to delve within the subject to reveal its inner nature, instead of standing before it and observing its outward reflection.

In the late 19th century, the ideas of Sigmund Freud and many philosophers seemed to complement discoveries in mathematics, astronomy and science to reshape the Western view of humanity and our place in the universe.

Eastern religion and Christian mysticism also pointed to an inner world beyond the merely visual or material.

Marcel Duchamp lost interest in creating art to be seen by the eye, and began making conceptual pieces. He made no declarations of what his art meant, leaving it to the viewer to discover or invent their own meaning.

In 1913-14 he made ‘3 Standard Stoppages’. The name was a satirical remark on the metric system, seeing it as a human mental construct rather than a universal absolute.

He dropped three 1-metre threads from a height of 1 metre onto stretched canvases. He mounted them onto glass and put them into a box originally made for a croquet set.

Around this time he also began to create ‘readymades’ such as an upturned bicycle wheel mounted on a box. ‘Fountain’ was his readymade ‘masterpiece’, called ‘art’ simply because the artist said it was art and because it was displayed as art in a gallery.

The narrative had moved away from telling stories on a flat plane. The viewer was no longer confined to discerning what the artist meant. Now there was the possibility, even the responsibility, to make one’s own connections and create one’s own meaning.

As quantum theory – an emerging concept at this time - suggests, an entity can either be a particle (matter) or a wave (the result of matter), depending on your point of view.

‘Fountain’ asked, “If the viewer is not looking, is it still art? Does the viewer by the act of viewing make it art? In the end, can reality ever be described? Is matter inconsequential if existence is the relationship between matter, not the matter itself? Or does matter define the relationship?”

At this time, Wassily Kandinsky too was leaving visual language behind and returning to the primordial. Many of the Dadaists went on to Surrealism, which fused waking thought with dream consciousness. These movements and all that have followed have attempted to describe the non-physical world and the essence or origin.

Dada can be seen either as the beginning of the post modern world, the end of the Renaissance - the rebirth of classicism - or the confluence of scientific methods with religion and philosophy. It can even be understood as the closing of the circle - which by definition has no beginning or end - of humanity’s voyage of artistic discovery.

Sean De Siun